For the last three decades, Africans have been driven out of the continent for lack of opportunities and a dwindling educational system. Both are highly orchestrated by the poor political leadership and internal economic saboteurs. Media, one of the critical components of the continent when it comes to pushing its image, is not helpful in taming the migration tide because of the constant reportage of positive happenings in developed countries and negative incidents on the continent.

Nevertheless, according to many business-oriented, regional, and global reports, the movement has delivered huge benefits to the continent during these decades when one looks at the growth of cash remittances to the different sub-regions of the continent. The statistics are really staggering; however, they point to the fact that Africans at home are getting financial support from their sisters, daughters, mothers, and fathers in the diaspora. In its latest report, the World Bank notes that Sub-Saharan Africa received an estimated US$49 billion in remittances in 2021.

The African Digital Remittances segment is expected to grow by 9.15% (2023-2027), resulting in a market volume of US$2.22 billion in 2027. The importance of remittances from abroad for African economies is well known. A total of $95.6 billion is estimated to flow into the continent each year. Also, remittances to LMICs are expected to total $5.4 trillion by 2030. The majority of these resources will be used by remittance-receiving families to achieve their own personal goals, such as increasing income, accessing better health and nutrition, having educational opportunities, improving housing and sanitation, entrepreneurship, and lifting them out of poverty.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

The examination of the senders of these remittances by our analysts from different sources indicates that African students in various universities are not left out of contributing to the growth. A number of the students work and study at the same time. It is surprising that African students constitute a relatively large percentage of foreign students in most developed countries. Our check reveals that the general trend of the student’s mobility from the continent aligns with her colonial masters’ path. For instance, most British colonised countries prefer the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries in the global north, while students from Cameroon, Benin Republic, and other French colonised nations go to France and other French or Portuguese-speaking countries in the same region (global north).

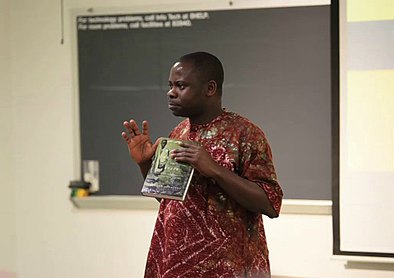

As the developed world attracts African students, it also does not relent in having African academics, both those who schooled on the continent and those who became academics after their studies. In all these areas, Africa is sitting on cash and intellectual capital, with little exploration of the latter to really spur the growth and development of the continent. Whether we call it an intellectual asset or capital, Africa can benefit from intellectual remittance in the form of human capital, relationship capital, and structural capital. It is when political and business leaders really tap into these that Africa can be what it is supposed to be, based on abundant natural and human resources. This has been the position of our analyst over the years, which has recently been reemphasized through the intellectual prism of Professor Saheed Aderinto, a Nigerian-American Professor of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at Florida International University. The professor’s view is reproduced below.

My lecture focused on Intellectual Remittance—the undervalued, underreported, and underappreciated transfer of knowledge and collaboration between Nigerian scholars at home and their diaspora counterparts. I emphasized that the overwhelming concentration on cash remittance has blurred our focus on the unquantifiable wealth in the invisible labour of scholars—Blacks, Whites, among many diverse racial backgrounds and identities—working selflessly behind the scenes with Nigeria-based scholars to build interpersonal relationships that break retrogressive bureaucracy and leverage on technology to provide supplemental, yet valuable, support for research and training in Nigerian higher institutions.

The difficult part of the lecture is not explaining the meaning of intellectual remittance to a highly educated audience—it’s connecting global intellectual collaboration, especially in the humanities and social sciences, to real cash remittance that policymakers understand as the drivers of development on the African continent. It’s improper and impossible to put a monetary value on intellectual wealth; yet, explaining the cumulative and reverberatory implications of intellectual remittance over decades and generations establish my position that cash remittance shouldn’t be ranked higher than intellectual, simply because we can’t valuate, feel, or see it. Indeed, in numerous cases, intellectual remittance is the foundation on which cash remittance is built. Without it, the millions of cash remittance that attracts public attention and formed the basis of development discourses wouldn’t exist in the first place.