Yes, it has been a long four years since I posted a piece entitled “Pop Culture Africa: Review of Creativity in the Music Industry” on LinkedIn.

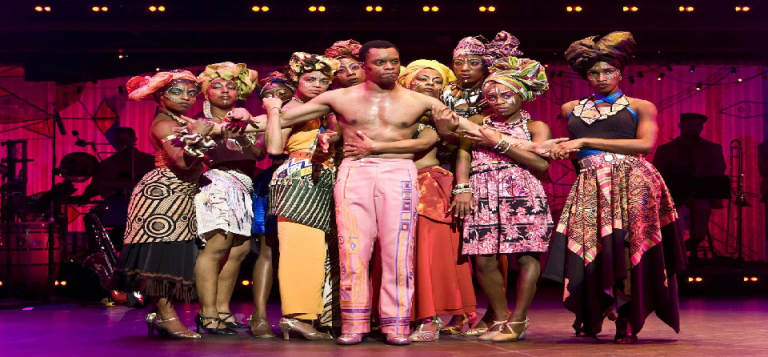

In that post I highlighted my an interesting encounter of a display at the British Library in the King’s Cross area of London, which featured the image of Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the king of Afrobeat (yes, without the “s”) and acclaimed President of the masses. My encounter of the billboard was based upon my daily commute into London (at the time) since taking up a job in the knowledge quarter in September 2015.

Talking about Fela, the man has been misunderstood by many, incarcerated for his political views and wayward lifestyle, but still revered for his creativity as far as music goes. Following this observation, I unpacked my 5-point confession as follows:

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

- I bought my first book on Amazon only last week.

- I have started paying attention to non-academic texts after reading this book (calm down, I will reveal the title and author in due time).

- I have now read the article on The DIY Artist for the umpteenth time (this morning was the most recent read).

- My discovery of Dr Modupe Faseke is dejavu as I have now discovered Professor Sonny Oti author of a must read entitled Highlife in West Africa (yes that’s the book I recently bought on Amazon).

- My call for papers highlighting the creativity of African artists in 2014.

Following this encounter, I had sought, albeit all but given up on the plan to exploit this observation in a special issue of a scholarly journal, which was subsequently pulled from the African Journal of Business & Economic Research special issue on “Entrepreneurship in the creative industry in Africa.”

“…creative entrepreneurs from Africa have changed the way music is viewed by tapping into political issues in the European Union and utilising their own innovative marketing campaigns. The rising economic powerhouses of countries in Africa including Nigeria and Ghana have exported creative entrepreneurs to Western Europe and the United States [to the extent that] the entrepreneurship occurring within the creative industry [in Africa] surpasses that in many developed countries due to the role of innovation and creativity.”

The DIY (do-it-yourself) artist was written introspectively in the same manner Oti’s book traced the roots of Highlife music in Africa. What’s more, Professor Sonny Oti did provide some exposition on the creativity of Fela – whom the British Library has found endorsement value in, as a main dish in celebrating Africa over the course of 4 months – 16 October 2015-16 February 2016.

Just a few quotes to underline my posturing here. Citing texts from Carlos and Shawna Moore’s biography of Fela, Sonny Oti points out:

“This …is not just a biography of a celebrity… then everything about this volcanic music called Afro Beat and the tumultuous, tormented life of its creator speaks to and about the lives, struggle and hopes of hundreds of millions of men and women […] in Africa.”

He also talks about the non-conformist individual and his music posing some rather interesting questions:

“Is Fela Anikulapo Kuti a rebel, a radical and revolutionary? Alternatively, is he a confrontationalist, a deviant and an alarmist… troublemaker… non-conformist… a critic who enjoys threatening established authority? The answers to these questions may be provided by his song-texts […] one thing is certain about him. No one who knows him well enough can ever think of tagging the phrase ‘criminal’ along with his name without really disbelieving himself.”

So enough of Afrobeat for a moment and highlighting the genesis in highlife. According to Sonny Oti, the creativity in highlife have been found to contribute to national growth statistics. In his exploration of ‘the movement and the monument’ of highlife, for instance, Oti points out that:

“…critics evaluate it as a popular music genre, but fail to emphasize that its critical song-texts are the major forces guaranteeing its development [and contributing to the] economic and national growth and stability in Africa […]. Highlife musicians may be referred to as modern African towncriers whose […] songtexts, like drama and theatre texts present not only Africa’s culture, but her social, economic and political problems.”

A similar trend is perpetuated in the case of other variants and mutations of African music from Afrobeats to Hiplife, which are often managed by individuals devoid of policy support. Nigeria’s Don Jazzy and his Mavins ensemble is a case in point.

Indeed, the Nigerian Music scene is replete with DIY artists, capturing both “creativity” and “fluidity” – something that is consistent with a local music scene of independents in the UK, as highlighted by Paul Oliver in 2010:

“The independent (DIY) artist that inhabits a local music scene has a strong ethic that relates back to the punk ideals of being creative and having fun whilst at the same time being self-sustainable. In terms of infrastructure the local music scenes are extremely difficult to define as they are quite fluid and free flowing and are not like a typical organisation.”

As Oliver points out in his article entitled “The DIY artist: issues of sustainability within local music scenes”:

“In terms of academic writing, local music scenes have been relatively untouched. Therefore it is necessary to rethink the sub-sectors of the music industries and how they have changed in recent years […] Therefore, through a strong DIY ethic with an emphasis on creativity and self-management, a clear understanding of local music scenes and the DIY artist helps identify one of the key sub-sectors of the music industries as well as demonstrate that sub-cultures have value.”

Besides the piece by Christopher Okonkwo entitled “sound statements and counterpoints” featuring “Ike Oguine’s channeling of music, highlife, and Jazz in A Squatter’s Tale, one Emaeyak Peter Sylvanus has written about a similar topic not once, “Popular music and genre in mainstream Nollywood”, but twice “Prefiguring as an indigenous narrative tool in Nigerian cinema: An ethnomusicological reading” in the last 12-15 months.

A further illustration of these sound statements is captured in an article in the New York Times, entitled “The New Guard of Nigerian Musicians,” which showcased performers making their mark in a crowded field.

“Afrobeats, as contemporary African music is classified in foreign spaces, is gaining more recognition as an influential genre, as homegrown stars like Wizkid, Burna Boy and Davido are beginning to experience commercial success [to the extent that] “both Wizkid and Burna Boy contributed to the recent Beyoncé-produced “Lion King” album.”

Such internationalisation exploits are also confirmed in a recent World Remit (yes, the global remittance firm) report entitled “8 famous Nigerians who found international recognition”, where 50 percent were found to be Nigerian music crooners such as Wizkid, Yemi Alade, Tiwa Savage, D’Banj featuring alongside the likes of household names like Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (a former minister of finance), Victor Moses (a n international footballer), Hakeem Olajuwon (another sports personality and much-celebrated basketballer) and Agbani Darego ( a beauty queen).

Now to the article to which my addendum is targeted, “The Felabration of the King” by Nnamdi Odumody can be used to promote Nigeria as a global cultural and tourism destination, boosting [its] non-oil exports. In that article, Odumody (my namesake) highlights 8Cs equality split into two broad categories – collaboration (with a range of stakeholder groups) and creation (across platforms from Apps, animation, video game and theme parks) as follows:

- 1. Collaboration with the Federal and Lagos State Governments.

- 2. Collaboration with Foreign Airlines.

- 3. Collaboration with Electronic Commerce Brands.

- 4. Collaboration with Digital Media Platforms.

- 5. Creation of Felabration App accessible on all Mobile Platforms.

- 6. Creation of Fela Animated Movie.

- 7. Creation of Fela Video Game.

- 8. Creation of Fela Theme Park.

Taking this discourse a step further, another article by Ngozi Kolapo entitled “How Nigerian musicians can create billion naira brands,” made some rather interesting claims such as:

“The Nigerian music industry is currently witnessing an exponential growth due to advances in technology which has made music production, sales, distribution of audio and visual content quicker compared to the era of the legends before this generation. Afrobeats which their genre has been christened is dominating the airwaves not just from Lagos to Johannesburg but also getting airplay in the far flung Caribbean Islands…”

Ultimately, the main pointers from the above include advances in technology, music production, sales and distribution, as well as internationalisation. All of these reflect trends in the Nigerian Film industry as articulated in my article “The Impact of New Media (Digital) and Globalisation on Nollywood.”

In summing up, perhaps it is time to rearticulate the Movie and the Music Industry as complementary entities for the advancement of the creative industry in Nigeria in particular, and sub-Saharan Africa at large.