When Nigeria discovered crude oil in Oloibiri, Bayelsa, in 1956, political leaders and citizens believed that the resource would bring more abundance to everyone, regardless of gender, ethnicity, or religion. The early years of extracting oil and utilizing the revenue for socioeconomic advancement in all ramifications were not difficult, as expected. However, according to various sources, Nigeria began experiencing significant impediments that prevented her from generating expected revenue in line with daily production. Some people and groups felt that they were not receiving what was due to them from the national resource. The sources also establish how individuals and groups harmed and continue to disrupt resource production processes.

As previously stated, the disruption has resulted in a significant reduction in daily production. According to several reports, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited reported a number of barrels stolen by criminals worth billions of dollars. Despite the formation of the Joint Task Force, which includes the army, navy, air force, and mobile police, the criminals are succeeding. After determining the extent to which the force could address the challenge, the Federal Government hired the services of a security firm owned by one of the Niger Delta development activists. Government Oweizide Ekpemupolo, also known by his nickname Tompolo, owns the company.

A few days after the contract was awarded, local gangs and young people protested it, according to national media. Some social commentators and public affairs analysts believed that the protest was the work of saboteurs who had made money from illegal bunkering over the years.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

Meanwhile, our checks show that many potential solutions to the problem have been proposed in various studies conducted by academics and independent think tanks. For example, a study that examined the crime of crude oil theft between 2012 and 2014 produced a template that could be useful in reducing the problem. However, it appears that none of the stakeholders involved are prepared to find a long-term solution to the problem.

Public Concerns

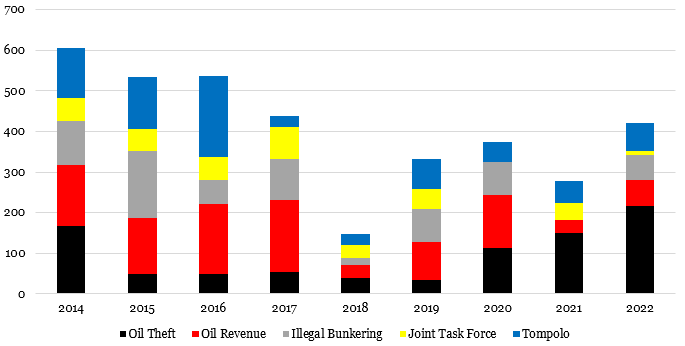

The examination of Nigerians who used the internet to learn about critical stakeholders and issues such as oil theft and illegal bunkering reveals some important insights for understanding the rediscovery of crude oil (oil theft) that was discovered 66 years ago. Nigerians, according to deep internet searches for information, are more concerned about oil theft in 2022 than they were in 2014 (see Exhibit 1). According to the analysis, they were more concerned about dwindling oil revenue in 2017 and 2016 than in other years during the government’s 9-year search for sources of oil theft.

In terms of whether the Joint Task Force, which includes the navy, army, police, and vigilantes, and Tompolo could stop the theft, our analysis shows that netizens (internet users) were more interested in seeing the security structure and Tompolo address illegal bunkering than the theft. However, our analysis shows that netizens were more interested in Tompolo’s abilities than in the security structure. According to our analyst, this outcome could be related to the recent contract awarded to Tompolo’s security firm, which has been widely reported in the news media. The Joint Task Force, on the other hand, appears to be appropriate for dealing with illegal bunkering, according to the analysis. Again, our analyst emphasizes that the outcome is consistent with existing facts establishing some positive results of the Force’s deployment of personnel to various locations in the Niger Delta Region over the years.

Exhibit 1: Nigeria’s Netizens Interest in Key Issues and Stakeholders between 2014 and 2022

Figuring the Elites as Fall-Guys

Our analysis of netizens who searched for information about oil theft and illegal bunkering, as well as what they read as factors for dwindling oil revenue, reveals that illegal bunkering must have been considered as a key factor prior to the recent ‘rediscovery of crude oil.’ According to the analysis, one percent of those who expressed an interest in illegal bunkering were more than 60% more likely to be aware of and consider illegal bunkering to be a dominant factor. Nigerians on social media have accused political elites and some individuals in the Niger Delta Region of being perpetrators in the same way that the news media has.

In an interview granted a foreign newspaper, Alexander Sewell, a research specialist, notes the complexity of tracking oil theft and illegal bunkering. According to him, illegal crude oil trafficking involves the military, surveillance companies, politicians and local communities.

“There are two ways to steal oil. The first is to connect a pipe to a pipeline to convey the product to a barge. The barge can then supply artisanal refineries or go back and forth to a larger vessel anchored in an area where the river is deeper. This vessel will then head out to sea to refuel a tanker bound for South America, Europe or Asia. These tankers can also stay close to the West African coast and carry out transactions with other vessels on the high seas.

The second option is the so-called topping, which is the act of adding a quantity of undeclared crude oil to an official shipment. In this case, the documents are in order, the permits have been issued and traffickers can resell the extra oil as if nothing had happened. This second method is very difficult to investigate, especially since it often involves officials and members of the political élite. It is really a way to steal and move huge quantities of oil for minimal risk.”