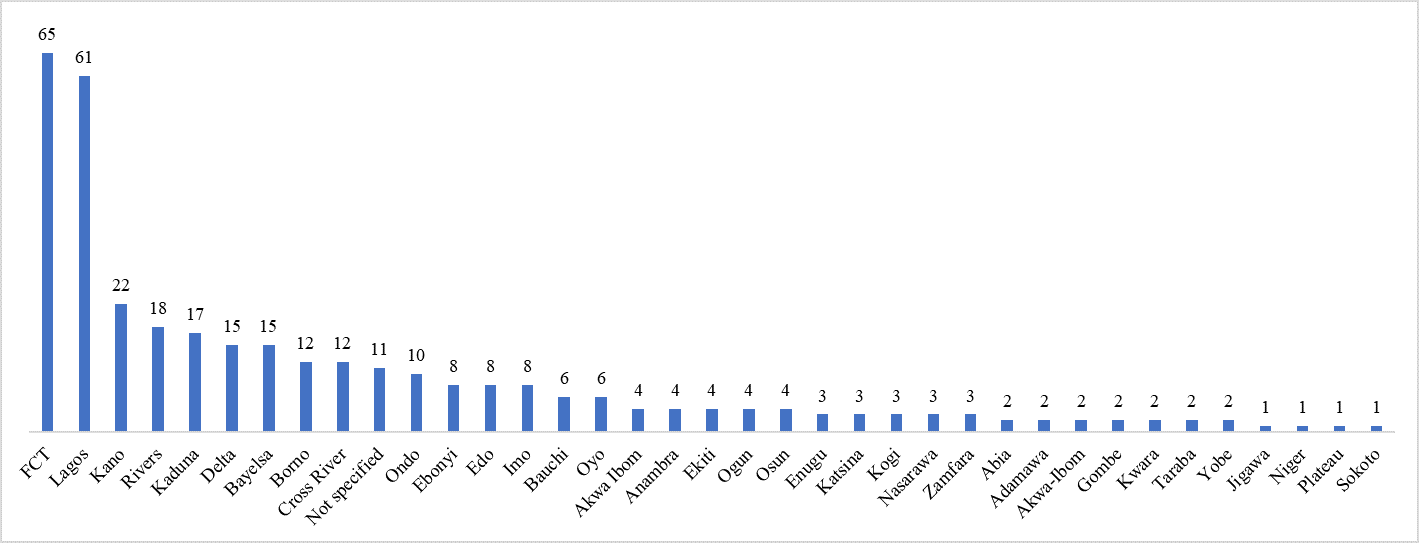

In any thriving democracy, the press serves as the conscience of the nation—a voice that speaks truth to power, holding governments, institutions, and individuals accountable. Yet, in Nigeria, the very act of journalism has increasingly become a dangerous endeavor. A chart mapping the number of attacks on journalists between January 2019 and August 2024 paints a grim picture of this reality. It reveals a disturbing trend of assaults, intimidation, and violence that is spreading across the country, leaving its marks in almost every state.

The numbers speak volumes. The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) tops the list with 65 attacks, closely followed by Lagos with 61. Together, these regions, which are the political and economic nerve centers of the nation, account for over 40% of the recorded incidents. These statistics are more than just figures—they tell a story of the mounting pressures faced by journalists who dare to report on governance, corruption, and the complex web of social and political challenges confronting Nigeria.

It is no coincidence that the FCT and Lagos are at the forefront of these attacks. Abuja, being the seat of political power, is the epicenter of governance, policymaking, and, often, corruption scandals. Journalists operating in this sphere face constant scrutiny and hostility from powerful interests who are intent on silencing critical voices. Lagos, on the other hand, is the nation’s media capital, home to many prominent news outlets and digital media platforms. Its vibrant press landscape, while commendable, also makes it a focal point for attacks, both physical and digital.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

Beyond these two hubs, states like Kano, Rivers, Kaduna, and Delta emerge as mid-tier zones of risk, reporting between 15 and 22 attacks each. These states, though not as prominent as the FCT or Lagos, have their unique challenges. Kano, a key political battleground in Northern Nigeria, often sees journalists caught in the crossfire of political rivalries and religious sensitivities. Rivers, with its history of electoral violence and oil-related conflicts, pose dangers for journalists covering politically charged issues. In Kaduna, a state grappling with ethno-religious crises and governance controversies, the media often bears the brunt of public and private frustrations.

What is equally troubling is the seeming quiet in states like Sokoto, Plateau, and Niger, which report just one attack each. At first glance, these numbers might suggest safer conditions for journalists, but this could also be a deceptive narrative. In many of these states, underreporting of attacks or self-censorship may mask the true extent of risks faced by journalists. The absence of vibrant media ecosystems in these regions could mean fewer documented cases, not necessarily fewer attacks.

The chart also sheds light on the broader sociopolitical environment in Nigeria. States plagued by insurgencies, like Borno, illustrate the dual threats faced by journalists—targeted by both insurgent groups and security forces who are often intolerant of critical coverage. Similarly, states with high incidences of political violence or contentious governance decisions create hostile environments for the press, where merely reporting the facts can result in threats, harassment, or worse.

But what do these numbers mean for Nigeria’s democracy? Journalism is the lifeblood of accountability and transparency. A free and independent press ensures that power is checked and that the voices of the marginalized are amplified. However, the prevalence of attacks on journalists paints a stark picture of a nation where press freedom is under siege.

The data suggests a culture of systemic impunity. Perpetrators of these attacks—whether state actors, political thugs, or other individuals—are rarely brought to justice. This lack of accountability emboldens others, creating an environment where journalists operate under constant fear. The result is a shrinking space for free speech, where self-censorship becomes a survival strategy. For every investigative report that remains unpublished, every story that is silenced, and every journalist forced into exile, Nigeria loses an opportunity to address its challenges and grow stronger as a nation.

The rise of digital journalism adds another layer to this crisis. While the internet has empowered journalists to reach wider audiences, it has also exposed them to new forms of threats. Online harassment, cyberbullying, and surveillance are now common, particularly for journalists in Lagos and the FCT. These attacks, though less visible, are no less damaging, often leading to psychological trauma and professional burnout.

So, what can be done to reverse this alarming trend?

First, Nigeria must prioritize the safety of its journalists. This begins with strong legal protections that ensure freedom of the press is not just a constitutional promise but a lived reality. Laws against press intimidation and harassment must be enforced, and perpetrators of violence against journalists must face swift and transparent justice.

Second, the media community must invest in capacity-building initiatives. Journalists, particularly those working in high-risk areas, need access to safety training and resources. Partnerships with international press organizations can provide valuable support, from legal aid to mental health services.

Third, there must be a concerted effort to raise public awareness about the importance of press freedom. The media plays a crucial role in promoting accountability, exposing corruption, and fostering national development. By educating citizens about these contributions, society can build a stronger collective resistance against attacks on the press.

Finally, technology must be leveraged to protect journalists. Tools such as encrypted communication platforms and cybersecurity training can help reporters navigate the digital threats they face. Media organizations should also adopt policies that prioritize the physical and digital safety of their staff.

The battle for press freedom in Nigeria is not just a fight for journalists—it is a fight for the soul of the nation. The numbers may be alarming, but they also serve as a wake-up call for action. As a society, we must decide whether we want to nurture a culture of transparency and accountability or allow the forces of intimidation and suppression to prevail.

The safety of journalists is the litmus test of any democracy. If Nigeria is to fulfill its potential as a leader on the African continent, it must ensure that those who seek to tell its stories, however uncomfortable they may be, can do so without fear. In protecting its journalists, Nigeria protects its democracy.