EU-Banned Pesticides Still Poisoning South African Farm Workers: Calls Grow to End Toxic Exports

Quote from Alex bobby on April 6, 2025, 5:06 AM

“Enough Is Enough”: South Africa’s Farm Workers Call Out Europe’s Toxic Pesticide Exports

For over four decades, Dina Ndelini toiled under the sun in the vineyards around Cape Town, contributing to South Africa’s thriving wine industry. But her life was upended when a sudden bout of breathlessness led to a devastating diagnosis. Her doctor pointed to exposure to Dormex, a chemical used on vineyards and banned in the European Union since 2009 for its high toxicity. Like many South African farm workers, Dina became a silent casualty of a trade system that exports dangers deemed too unsafe for Europe to countries with weaker protections.

Dormex, whose active ingredient is cyanamide, is just one of the many highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs) still exported from Europe to countries like South Africa. While banned in the EU for over a decade, it remains legally used on South African soil—largely on farms that export food right back to European consumers.

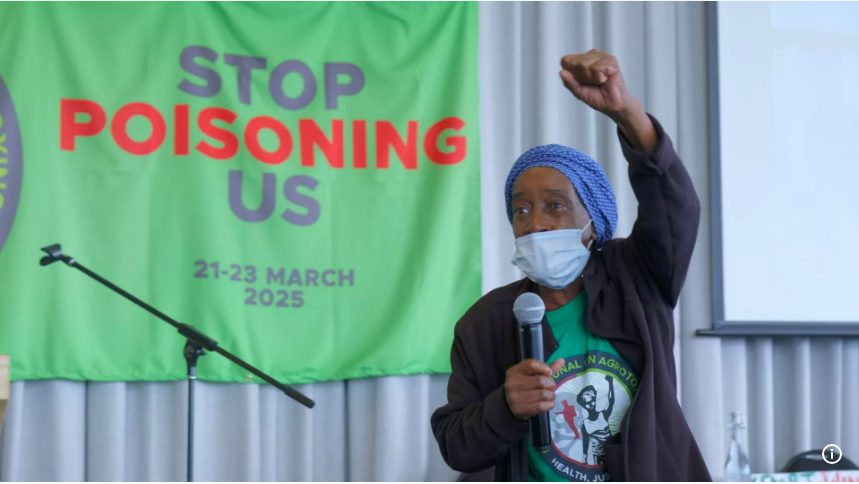

At a recent People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins held in Stellenbosch, farm workers, legal experts, and health professionals gathered to spotlight this injustice. While the tribunal has no formal legal power, it serves as a critical platform for the marginalised voices of farm labourers who face the harshest consequences of pesticide exposure.

The message from South Africa’s farm workers to Europe was resounding: “Enough is enough.” Dina Ndelini, along with many others, called on European policymakers to end the export of hazardous chemicals to the Global South. “We don’t want these pesticides from Europe anymore,” she stated.

The testimonies were harrowing. Farm workers spoke of severe lung damage, ovarian cancer, impaired vision, and other long-term health effects. “If it’s not good enough for Europeans, why do they think it’s good enough for us?” one anonymous worker asked, highlighting the stark injustice and double standard at play.

According to the African Centre for Biodiversity, 192 highly hazardous pesticides are still in legal use in South Africa—57 of which are banned in the EU. These chemicals are often carcinogenic, neurotoxic, or acutely harmful to the environment. Yet, the people exposed to them daily—mostly Black and Coloured farm workers—remain the most economically vulnerable in a nation still reckoning with its apartheid legacy.

Women bear the brunt of this burden. The Women on Farms Project (WFP) notes that not only are women more biologically vulnerable to pesticide exposure, but they are also socially disadvantaged, often lacking access to protective equipment or even basic sanitation on farms. At the tribunal, workers testified to wearing scarves over their faces and lacking water or toilet access while handling toxic sprays.

Despite global commitments to safer agriculture, the EU continues to export these banned pesticides—an act the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Dr. Marcos Orellana, decried as a “blatant double standard.” He stressed that the human body is the same everywhere. What differs is the structural inequality and the lack of resources in nations like South Africa to properly regulate or resist such exports.

European agrochemical lobby groups like CropLife argue that different agricultural conditions necessitate the use of these chemicals. But to farm workers and their advocates, this argument rings hollow. “There are alternatives,” insists Dr. Andrea Rother, head of the environmental health division at the University of Cape Town. She believes that an export ban from the EU could be the spark South Africa needs to transition to more sustainable farming.

Though South Africa has pledged to phase out highly hazardous pesticides, enforcement remains weak, and many farm workers are unaware of their rights or hesitant to speak out. Legal protections and international treaties like the Rotterdam Convention are often too slow or bureaucratic to offer timely safeguards. Dr. Rother describes the convention as little more than a “tickbox exercise” that rarely results in meaningful change.

WFP campaigner Kara MacKay argues that Europe’s continued pesticide exports are not just a legal or regulatory issue—they are a moral one. “Each day the EU continues this trade, it is complicit in the daily pesticide poisoning of farm workers,” she says. “To argue any differently reveals a racist and colonial thinking that is unjustified.”

The People’s Tribunal will deliver its findings and legal recommendations in the coming months. But for the farm workers of South Africa, the message is already clear: this toxic trade must end. The wine flowing into European glasses may be celebrated for its flavour, but behind each bottle are the lives of labourers like Dina—sacrificed for profits and propped up by a global system in urgent need of reform.

Conclusion

The case of Dina Ndelini and countless other South African farm workers sheds harsh light on a troubling global injustice: the continued export of dangerous, EU-banned pesticides to developing nations. Despite Europe recognising the health and environmental dangers of chemicals like Dormex, they are still being manufactured and shipped to countries like South Africa, where regulation is weaker, protections are minimal, and vulnerable communities bear the brunt of exposure.

The testimonies shared at the People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins reveal not just the physical harm caused by these chemicals but also the broader systemic issues at play—colonial legacies, economic inequalities, and corporate influence over agricultural practices. For the EU, continuing to export what it deems too toxic for its own citizens sends a clear message of double standards and disregard for human rights beyond its borders.

As South African workers and advocates call for an end to this “toxic trade,” the time has come for Europe to listen. True progress means not only banning harmful chemicals at home but also ensuring they are not harming others abroad. Anything less is not just a regulatory failure—it’s a moral one.

“Enough Is Enough”: South Africa’s Farm Workers Call Out Europe’s Toxic Pesticide Exports

For over four decades, Dina Ndelini toiled under the sun in the vineyards around Cape Town, contributing to South Africa’s thriving wine industry. But her life was upended when a sudden bout of breathlessness led to a devastating diagnosis. Her doctor pointed to exposure to Dormex, a chemical used on vineyards and banned in the European Union since 2009 for its high toxicity. Like many South African farm workers, Dina became a silent casualty of a trade system that exports dangers deemed too unsafe for Europe to countries with weaker protections.

Dormex, whose active ingredient is cyanamide, is just one of the many highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs) still exported from Europe to countries like South Africa. While banned in the EU for over a decade, it remains legally used on South African soil—largely on farms that export food right back to European consumers.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 17 (June 9 – Sept 6, 2025) today for early bird discounts. Do annual for access to Blucera.com.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register to become a better CEO or Director with Tekedia CEO & Director Program.

At a recent People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins held in Stellenbosch, farm workers, legal experts, and health professionals gathered to spotlight this injustice. While the tribunal has no formal legal power, it serves as a critical platform for the marginalised voices of farm labourers who face the harshest consequences of pesticide exposure.

The message from South Africa’s farm workers to Europe was resounding: “Enough is enough.” Dina Ndelini, along with many others, called on European policymakers to end the export of hazardous chemicals to the Global South. “We don’t want these pesticides from Europe anymore,” she stated.

The testimonies were harrowing. Farm workers spoke of severe lung damage, ovarian cancer, impaired vision, and other long-term health effects. “If it’s not good enough for Europeans, why do they think it’s good enough for us?” one anonymous worker asked, highlighting the stark injustice and double standard at play.

According to the African Centre for Biodiversity, 192 highly hazardous pesticides are still in legal use in South Africa—57 of which are banned in the EU. These chemicals are often carcinogenic, neurotoxic, or acutely harmful to the environment. Yet, the people exposed to them daily—mostly Black and Coloured farm workers—remain the most economically vulnerable in a nation still reckoning with its apartheid legacy.

Women bear the brunt of this burden. The Women on Farms Project (WFP) notes that not only are women more biologically vulnerable to pesticide exposure, but they are also socially disadvantaged, often lacking access to protective equipment or even basic sanitation on farms. At the tribunal, workers testified to wearing scarves over their faces and lacking water or toilet access while handling toxic sprays.

Despite global commitments to safer agriculture, the EU continues to export these banned pesticides—an act the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Dr. Marcos Orellana, decried as a “blatant double standard.” He stressed that the human body is the same everywhere. What differs is the structural inequality and the lack of resources in nations like South Africa to properly regulate or resist such exports.

European agrochemical lobby groups like CropLife argue that different agricultural conditions necessitate the use of these chemicals. But to farm workers and their advocates, this argument rings hollow. “There are alternatives,” insists Dr. Andrea Rother, head of the environmental health division at the University of Cape Town. She believes that an export ban from the EU could be the spark South Africa needs to transition to more sustainable farming.

Though South Africa has pledged to phase out highly hazardous pesticides, enforcement remains weak, and many farm workers are unaware of their rights or hesitant to speak out. Legal protections and international treaties like the Rotterdam Convention are often too slow or bureaucratic to offer timely safeguards. Dr. Rother describes the convention as little more than a “tickbox exercise” that rarely results in meaningful change.

WFP campaigner Kara MacKay argues that Europe’s continued pesticide exports are not just a legal or regulatory issue—they are a moral one. “Each day the EU continues this trade, it is complicit in the daily pesticide poisoning of farm workers,” she says. “To argue any differently reveals a racist and colonial thinking that is unjustified.”

The People’s Tribunal will deliver its findings and legal recommendations in the coming months. But for the farm workers of South Africa, the message is already clear: this toxic trade must end. The wine flowing into European glasses may be celebrated for its flavour, but behind each bottle are the lives of labourers like Dina—sacrificed for profits and propped up by a global system in urgent need of reform.

Conclusion

The case of Dina Ndelini and countless other South African farm workers sheds harsh light on a troubling global injustice: the continued export of dangerous, EU-banned pesticides to developing nations. Despite Europe recognising the health and environmental dangers of chemicals like Dormex, they are still being manufactured and shipped to countries like South Africa, where regulation is weaker, protections are minimal, and vulnerable communities bear the brunt of exposure.

The testimonies shared at the People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins reveal not just the physical harm caused by these chemicals but also the broader systemic issues at play—colonial legacies, economic inequalities, and corporate influence over agricultural practices. For the EU, continuing to export what it deems too toxic for its own citizens sends a clear message of double standards and disregard for human rights beyond its borders.

As South African workers and advocates call for an end to this “toxic trade,” the time has come for Europe to listen. True progress means not only banning harmful chemicals at home but also ensuring they are not harming others abroad. Anything less is not just a regulatory failure—it’s a moral one.

Uploaded files: