Data is a stubborn thing when it faces conventional wisdom. It often challenges our assumptions, biases and beliefs, and forces us to rethink our views and opinions. Data can also be a powerful tool for innovation, discovery and problem-solving, if we are willing to listen to what it tells us and act accordingly.

I will share some examples of how data has challenged conventional wisdom in various fields and domains, and how it has led to new insights, breakthroughs and opportunities. I will also discuss some of the barriers and pitfalls that prevent us from embracing data-driven decision making, and how we can overcome them.

One of the most famous examples of data challenging conventional wisdom is the story of Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician who worked in a maternity clinic in Vienna in the 1840s. He noticed that the mortality rate of women who gave birth in the clinic was much higher than those who gave birth at home or in other hospitals.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

He also observed that the doctors who delivered the babies often came from performing autopsies on corpses, without washing their hands or instruments. He hypothesized that the doctors were transferring some kind of “cadaverous particles” to the women, causing them to die from infections.

Semmelweis decided to test his hypothesis by requiring the doctors to wash their hands with a chlorine solution before attending to the women. He found that the mortality rate dropped dramatically, from 18% to 2%. He published his findings and tried to convince his colleagues to adopt his practice, but he was met with resistance and ridicule.

His idea contradicted the prevailing medical theory of the time, which attributed diseases to imbalances in the four bodily humors. Semmelweis was eventually dismissed from his position and died in an asylum, before his discovery was widely accepted and recognized as a major contribution to medicine.

Semmelweis’s story illustrates how data can challenge conventional wisdom, but also how difficult it can be to change people’s minds and behaviors based on data. Some of the reasons why people resist data are:

Confirmation bias: We tend to seek out and interpret information that confirms our existing beliefs and ignore or dismiss information that contradicts them. Status quo bias: We tend to prefer things to remain the same, and avoid changes that might disrupt our routines, habits or comfort zones.

Authority bias: We tend to trust and follow the opinions of experts, leaders or authorities, even if they are wrong or outdated. Groupthink: We tend to conform to the views and norms of our peers, colleagues or social groups, even if they are irrational or harmful. Fear of failure: We tend to avoid taking risks or trying new things that might lead to failure or criticism.

The first step is to challenge conventional wisdom. This involves questioning traditional investment advice and assumptions to see if they hold up under scrutiny. EBI seeks to find evidence that supports or disproves these assumptions to help investors make more informed decisions.

The second step is to ask meaningful questions. This involves identifying the key issues that investors face and asking questions that will help them make better decisions. For example, what is the best way to capture market returns? How much risk should an investor take on? What is the most efficient way to diversify a portfolio?

The third step is to apply the evidence. This involves analyzing the data and research to determine the best course of action. EBI uses a systematic, analytical, and scientific approach to evaluate investment options and make informed decisions.

The final step is to monitor for effectiveness. This involves tracking the performance of the portfolio over time and adjusting as needed. EBI recognizes that markets are dynamic and that investment strategies must evolve over time to remain effective.

These biases can prevent us from seeing the truth, learning from data, and making better decisions. They can also hinder innovation, creativity and progress. How can we overcome them? Here are some suggestions:

Be curious: Seek out new information and perspectives that challenge your assumptions and expand your knowledge.

Be humble: Admit when you are wrong or don’t know something and be open to feedback and correction. Be critical: Question everything, including your own beliefs and opinions, and look for evidence and logic to support them. Be experimental: Test your ideas and hypotheses with data and learn from your successes and failures. Be collaborative: Share your data and insights with others and seek their input and opinions.

Data is a stubborn thing when it faces conventional wisdom. But it can also be a catalyst for change, improvement and growth. If we are willing to embrace data-driven decision making, we can unlock its potential and benefit from its power.

Telcos make more Yields from poor areas with Data plans than rich areas in Accra

This is a surprising fact that many people may not be aware of. How can it be that the poor areas of Accra, where most people struggle to afford basic necessities, are more profitable for the telecommunication companies than the rich areas, where people have more disposable income and access to better infrastructure?

The answer lies in the data plans that the telcos offer to their customers. In the poor areas, most people rely on mobile phones as their primary means of communication and information. They use data bundles that are cheap and expire quickly, such as daily or weekly plans. These plans have high per-megabyte rates and low data caps, which means that the customers end up paying more for less data.

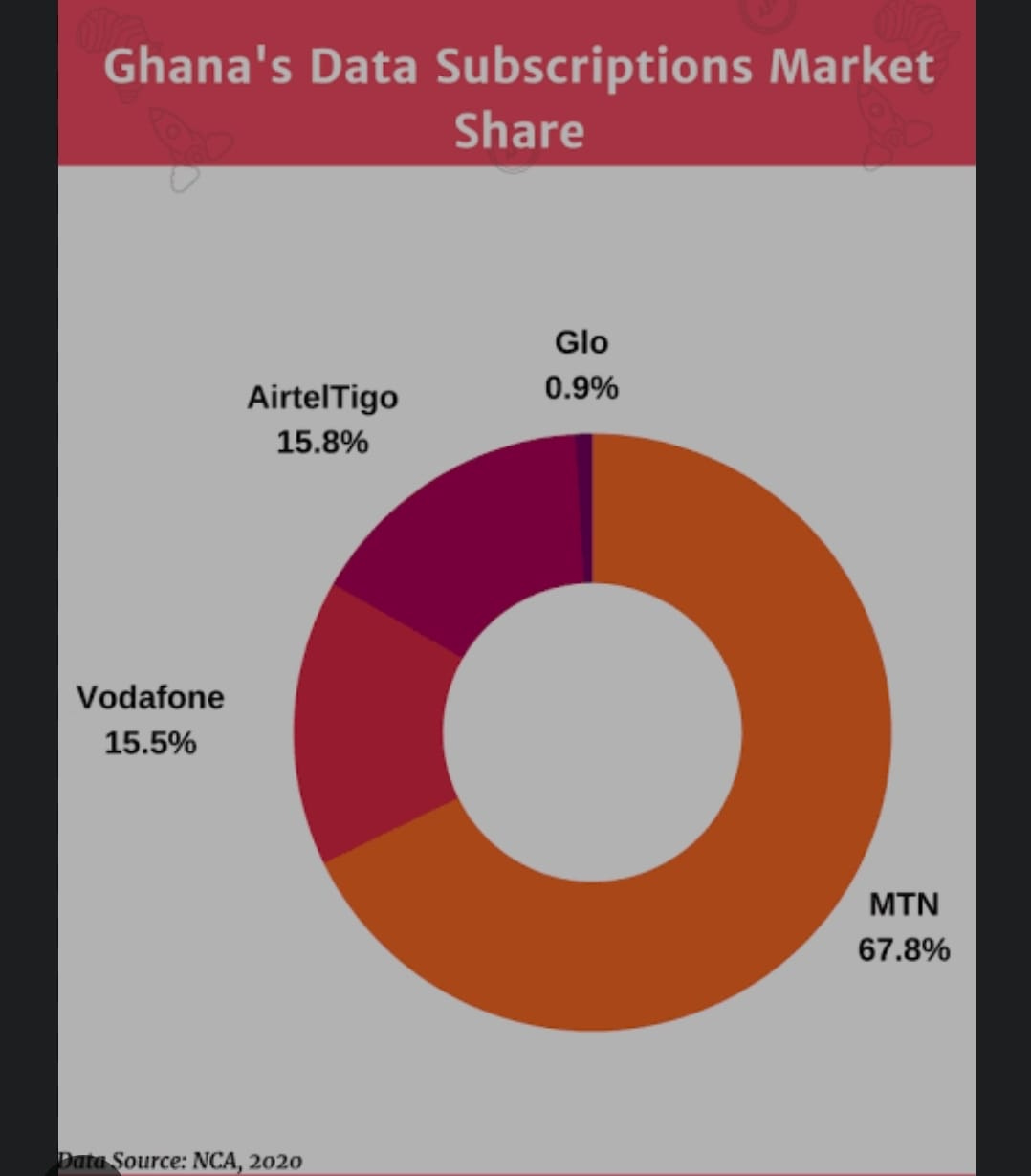

All Ghana’s networks have millions of dollars in assets and subscribers under their belt, but MTN Ghana takes the cake when it comes to the richest. As of 2020, they banked approximately 21 million subscribers, which translates to a whopping 53% market share in terms of telecom companies in Ghana.

In contrast, in the rich areas, most people have access to other forms of communication and information, such as landlines, broadband internet, cable TV, etc. They use data bundles that are more expensive and last longer, such as monthly or yearly plans. These plans have lower per-megabyte rates and higher data caps, which means that the customers end up paying less for more data.

The telcos exploit this difference in demand and supply by charging different prices for different areas. They charge more for the poor areas, where there is high demand and low supply of data, and less for the rich areas, where there is low demand and high supply of data. This way, they maximize their profits by extracting more money from the poor customers than from the rich ones.

Policy makers pushing for digitalization.

For years now, policy makers have been pushing for economic progress through digitalization. Successive governments have initiated a number of projects aimed at connecting more people to the Internet. In 2004, Ghana finalized and legally adopted its ICT Policy for Accelerated Development (ICT4AD), which outlined its vision for the information age. However – and this is the flip side of the coin – digital improvements are predominantly benefiting high earners in urban areas or companies based along the fiber optic infrastructure.

Even in the capital, Accra, coverage is still fragmented, and, especially for start-ups, far too expensive, as William Will Senyo, co-founder and CEO of Impact Hub Accra explains: “There is high speed Internet, but it costs an arm and a leg. It costs you $15 to $100,000 dollars a year to have somewhere between 50 and 100 mbps stable high-speed fiber Internet. So how many companies can afford that? Very few.”

Even for people with a regular income, access to the Internet – and with it the opportunities for digital participation – is associated with high costs. That’s despite Ghana’s leadership among its neighbors. The price for 1GB of mobile data volume is just over 2 percent of an average monthly income. In an international comparison by the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI), Ghana ranks 20th out of 60 countries surveyed. The A4AI Affordability Drivers Index summarizes several factors relevant to access.

Regina Honu, CEO of Soronko Academy, which runs the Tech Needs Girls mentorship program where they teach primarily women and girls to code and work with technology, also remarks that digital participation in Ghana remains difficult because “the cost is prohibitive.” She hopes that “government initiatives that use the internet to train more people in different places and get more organizations to come in” will drive down the cost.

The government is aware of the problem of cost. Ghana was the second nation to endorse the “1 for 2” Internet affordability target. In 2017, Communications Minister Ursula Owusu-Ekuful announced Ghana’s intention to start working toward “1 for 2,” meaning, 1GB of mobile broadband for 2 percent or less of an average monthly income.

This is a clear example of how the telcos are taking advantage of the digital divide in Accra. They are not providing equal and affordable access to data for all their customers, but rather discriminating based on their location and income level. This is unfair and unethical, and it needs to change.