Contrary to popular belief, the gap between rich and poor continues to get smaller. This is the main argument of a new book by economist Steven Pinker, who claims that the world is becoming more equal and prosperous than ever before. I will examine some of the evidence and arguments that Pinker presents and evaluate how convincing they are.

Pinker’s main source of data is the World Bank, which tracks various indicators of poverty, inequality, and human development across countries and regions. The World Bank data is based on household surveys, national accounts, and other sources that measure the income and consumption of people around the world.

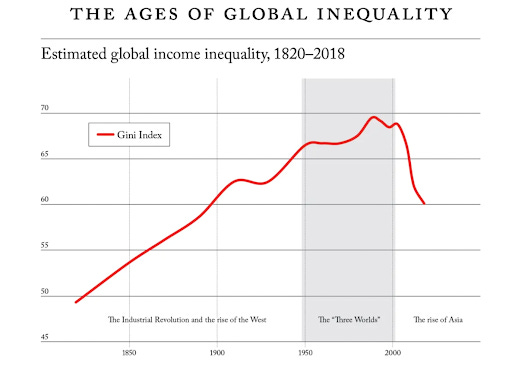

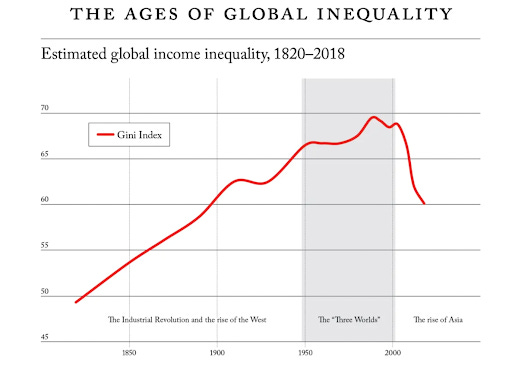

The World Bank uses a standard poverty line of $1.90 per day, which is adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) to reflect the different costs of living in different countries. The World Bank also calculates the Gini coefficient, which is a measure of how evenly income is distributed within a country or region. A Gini coefficient of zero means perfect equality, while a Gini coefficient of one means perfect inequality.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026): big discounts for early bird.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment (next edition begins Jan 24 2026).

According to Pinker, the World Bank data shows that the global poverty rate has fallen from 42% in 1981 to 10% in 2015, meaning that more than a billion people have escaped extreme poverty in the past three decades.

Moreover, Pinker argues that the global income distribution has become more equal, as the share of income going to the richest 1% has declined from 16% in 1980 to 14% in 2016. He also points out that other measures of well-being, such as health, education, democracy, and human rights, have improved significantly for most people around the world.

Pinker’s optimistic view of global progress is not shared by everyone. Some critics have challenged his use and interpretation of the World Bank data, arguing that he ignores important nuances and limitations of the statistics. For example, some scholars have argued that the global poverty line of $1.90 per day is too low and arbitrary, and that using a higher threshold would show a much larger and persistent number of poor people in the world.

Others have pointed out that the global income distribution is still highly skewed and unfair, as the richest 1% still own more than half of the world’s wealth, and that income inequality within countries has increased in many cases.

Furthermore, some critics have questioned Pinker’s causal claims about the drivers of global progress, suggesting that he overstates the role of free markets and liberal democracy, and understates the role of social movements and public policies.

Pinker’s book offers a provocative and controversial perspective on the state of the world today. While he presents some compelling evidence and arguments to support his claim that the gap between rich and poor is getting smaller, he also faces some serious challenges and criticisms from alternative viewpoints. Ultimately, the debate about global inequality and progress is not only about facts and figures, but also about values and visions for the future.